11 December 2024–Military vehicles rumbling toward the presidential palace, bombs dropped by the Chilean Air Force, and an eerie quiet descending over Santiago after a curfew imposed by a military junta—a lone seismometer captured all these features of the 1973 Chilean coup d’état.

In Seismological Research Letters, Sergio León-Rios of Universidad de Chile and colleagues share the story told on the fragile thermal paper of these historical seismograms, and discuss how these seismograms and others should be preserved and studied for their scientific and cultural significance.

The researchers began analyzing the September 1973 seismograms in 2023. “It was just after the 50th commemoration of the coup, and a lot of activities were going on around the country,” said León-Rios. “So finding these records was something that we saw as another perspective to describe what happened in the days around the coup.”

The analysis is part of Herencia Sísmica, a project that has brought together scientists and artists, including the team of authors on the SRL paper, “to give both scientific and cultural value to the historical record of disasters in Chile,” León-Rios said.

The seismograms were recorded by a single electromagnetic seismometer installed 2 kilometers away from Palacio de La Moneda, the seat of the president in the Chilean capital of Santiago. The researchers paired the seismic data with historical accounts of the September 1973 coup from the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos.

The data show an abrupt drop in ambient seismic noise on 11 September 1973, as La Moneda was surrounded by vehicles and a radio bulletin warning people to stay at home disrupted the morning routines of santiaguinos. Later in the day, the seismic record captured the signals caused by the Chilean Air Force flying over the city center and bombing La Moneda, as well as the signal of heavy vehicles moving from a nearby military base toward the palace.

After the government was overthrown, the military junta established a nationwide curfew. The level of seismic noise captured by the seismometer dropped considerably with the announcement, the researchers found.

“What impressed me the most, and I can say that what also impresses people who see these seismograms for the first time, are the differences in the anthropogenic noise before and after the coup,” said León-Rios. “To see how the city goes from seismic noise representing regular activity to almost complete silence due to the national curfew after the coup is something that is very impressive to see.”

In the anthropogenic hush imposed by the curfew, the seismometer recorded three small earthquakes.

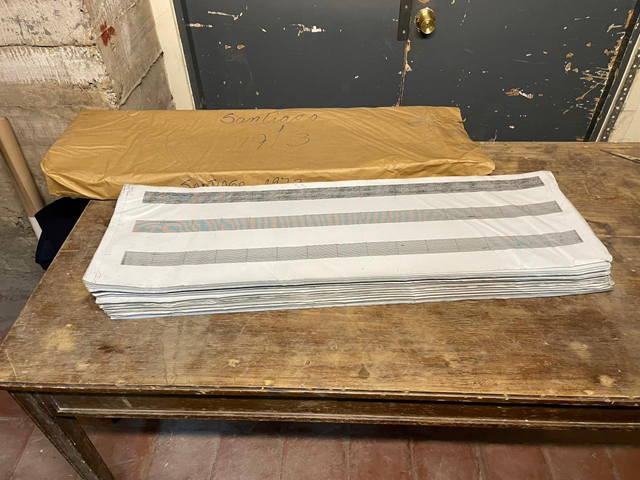

The thermal paper used for the 1973 seismograms was stored in a warehouse at Universidad de Chile. After the 1985 magnitude 8.0 Valparaíso earthquake, a machine for preparing smoked paper overheated and caused a fire in the warehouse. Diana Comte, a geophysics professor at the university and a co-author of the SRL paper, noticed the smoke and helped unplug the machine, saving many of the seismograms stored in the warehouse.

Chile’s long scientific history of earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions and other socio-natural disasters are part of the country’s cultural heritage as well, the authors note. Herencia Sísmica scientists and the artists at Chile’s Centro de Investigación para la Gestión Integrada de Riesgo de Desastres hope to preserve “not only paper records of earthquakes, but also data sheets from seismological stations, paper mail with data sent to and from all over the world, and seismic bulletins,” said León-Rios.

The team will display these materials, along with new artwork inspired by the records, in an art exhibition that they hope will be funded in January 2025.

“We, as inhabitants of this always-shaking-country, manage to have a social scale for earthquakes, and people can even guess the magnitude of an earthquake just by how they felt it, and that is something great,” León-Rios said. “But in terms of giving these records the importance they deserve, I think we need to work harder.”

“First, to get funding to preserve the records as well as possible,” he explained. “Second, to make them available to the community as a whole, because these records still contain relevant scientific information that can be analyzed with modern techniques, but they also contain memories and opportunities to get people talking about earthquakes, and with that, learn and be better prepared for future scenarios.”