9 April 2025— Plane crashes are thankfully rare, but when they happen, investigators rely on the airplane’s “black box” for data to explain what happened and how to prevent it in the future.

Seismic instruments deployed to gather strong motion data are kind of like those black boxes, said Keith Koper, director of the University of Utah Seismograph Stations. “The only thing they’re good for is if a big earthquake happens and you get really strong shaking.”

In 2020, the magnitude 5.7 Magna earthquake unleashed that strong shaking in Salt Lake City and as far away as Idaho and Wyoming. “And those instruments that we had been maintaining for decades, they paid off,” Koper said. “They told us about how the ground will actually move in a big earthquake, how particular buildings will move.”

“The data from that one earthquake is so valuable to engineers that they paid off all the decades of effort,” he added.

Decades of effort with an outsized payoff could also describe the Utah Seismograph Stations and the 12 other regional seismic networks throughout the United States. They operate 24/7 and offer services ranging from earthquake early warning to tours for Boy Scouts. They locate earthquakes and produce shaking maps within minutes of a fault rupture or volcanic eruption. They provide expert advice to local lawmakers about building codes and oil and gas production. They develop innovative network algorithms and research that are distributed worldwide.

Running these irreplaceable but often overlooked networks is also a juggling act, as SSA learned in recent interviews with network directors and staff seismologists. Budgets must include upgrades to system software and data storage, but they also need to cover gas money for the staff who repair seismic stations in remote forests and deserts. Networks need to hire system administrators who can handle the massive challenges of constant, real-time earthquake monitoring, but they need to do so with salaries that can’t always compete with industry.

“We’re the basic data that feeds into everything else, whether it’s the building codes or the seismic hazard maps or all of the science of trying to figure out why we have earthquakes, where they are,” said Mitch Withers, a research professor at the Center for Earthquake Research and Information at the University of Memphis. “We start with the raw data and that’s what the regional networks provide.”

Local Response, National Reach

The regional networks operate as part of the U.S. Advanced National Seismic System, which includes the National Earthquake Information Center and the National Strong Motion project along with a backbone of national seismic stations. Most regional networks receive significant federal funding, mainly through the U.S. Geological Survey, and some are operated in whole or in collaboration with the USGS, such as the regional networks on the U.S. West Coast and the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. These regional networks share valuable information, staff and research with the national earthquake readiness effort.

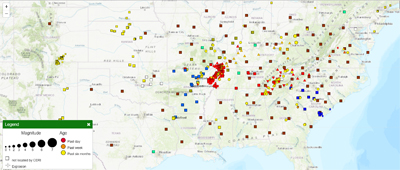

The regional networks operate dense webs of seismic stations in areas where there is moderate to high seismic hazard. This means that the regional networks can provide swift situational awareness to local and state emergency management agencies after an earthquake, said Withers.

Regional networks constantly exchange data and earthquake products with the USGS and sometimes with each other, said Jake Walter, a geophysicist and state seismologist at the Oklahoma Geological Survey. “Understanding the earthquake occurrence, location and magnitude of the events that are occurring within our operational region comes from our collaboration with the USGS.”

The networks collect and analyze data informed by the unique characteristics of their region’s seismic zone, so their information improves the overall accuracy of the national products produced for a specific earthquake, Withers noted.

Along with the traditional duties performed by a regional network, the Southern California Seismic Network also provides stations, data and researchers who work on earthquake early warning algorithms for ShakeAlert, the U.S. West Coast early warning system, said Gabrielle Tepp, a staff seismologist at the SCSN and Caltech. “Without our networks and without our data, there’s no ShakeAlert.”

Full-Service Seismology

There are media spokespeople, repair technicians, tour guides, teachers, technical experts, research scientists and public consolers inside each regional network.

The Oklahoma network often gets technical requests from the state’s oil and gas regulators, said Walter. “Often times, the regulatory body might be weighing a decision in which they get opinions from industry technical people, and they’re weighing that against our understanding of the ongoing seismic hazard in an area,” he explained.

SCSN maintains a strong public and media outreach program that includes a live seismograms feed and a live distributed acoustic sensing (DAS) array feed, said Tepp. “We are often called on for media interviews and press conferences after moderate or large earthquakes, and we have a lot of social media posting all the time.”

Network directors may work directly with government agencies during earthquakes, as Koper did with the Utah governor’s office during the Magna earthquake. “They want to know about, for instance, aftershocks and the possibility of another large earthquake, and which regions are most vulnerable,” he said.

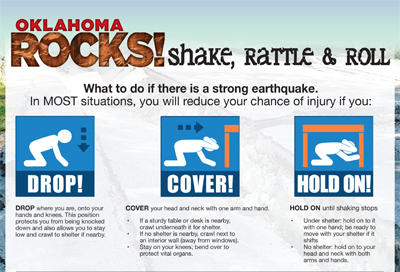

The networks often host tours and outreach events for schools and other groups, “demystifying earthquake science to kids of all ages,” as Walter said.

“I think it’s one of the most satisfying things that you can do as a person who works in science, to shed some light on things and explain it in a way that anybody can grasp,” he added.

“You know, when some woman in Ridgely, Tennessee calls me up because she felt something and we just had an earthquake, we can calm their fears,” Withers said. “That’s one of the big things we do. We can make people less concerned by providing them the information they need.”

Critical Investment Needed

Funding for the regional networks varies, but all of them rely on some federal dollars, whether for equipment upgrades, new software solutions or deploying rapid response teams to an earthquake.

CERI hopes to finish upgrading its oldest stations within the next five years, if federal funds remain available, said Withers. “We still operate many analog short period stations, which is old 1990s technology. So we’re trying to get that into the 21st century and with the help from the USGS, we’ve been making some really good progress on that.”

The Utah network gets about half of its budget from federal funds, mostly through the USGS but also through federal agencies such as the Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation, and the National Institute of Occupational Safety for monitoring and research at mining sites, said Koper. Since the network helps monitor seismic activity in the Yellowstone region, they also receive money from the USGS’ Volcano Hazards Program.

In Oklahoma, the state provides a significant amount of funding for the network, Walter said. He and his colleagues met with state legislators last year to speak about “the importance of state investment for our efforts, making sure that the oil and gas industry in Oklahoma is safely producing hydrocarbons, in addition to preparing for a future in which carbon storage might be an economy in Oklahoma.”

Recent federal funding freezes and especially the dismissal of federal workers across the USGS and other government agencies worry the regional network operators.

“There’s a lot of work that gets done by USGS civil servants, for example, in earthquake monitoring, that does benefit everybody in the science, in the field of earthquake science,” said Walter. “And I think that if those types of positions are imperiled, and these are often times people who are working at highest levels of government, I think there can be some trickle-down issues that will impact science for the next decade.”

Tepp said she has heard about restrictions from USGS field technicians associated with the SCSN “that effectively mean that they can’t get supplies, and they can’t travel overnight to repair sites. However, she also reported that policies are changing rapidly, including some “recent easements and work-arounds.”

Severe cuts to federal funding will prevent effective monitoring of the Intermountain West for earthquakes, said Koper. “We’ll only be able to detect and characterize the biggest earthquakes, and you need to be able to detect the little ones to figure out where the faults are.”

Monitoring of the Yellowstone supervolcano would “decay away pretty quickly if we lost that funding,” he added. “And again, it would be the same thing. You wouldn’t be able to notice all these small earthquakes that might be associated with magma moving around underground because you wouldn’t have the density of a local seismic network.”

Fewer federal funds and workers mean that “we would have fewer stations to do our job, we would be slower, we would miss more events, it would affect our 24/7 operations, it would affect the data distribution,” said Withers.

Despite their concerns, Withers and his colleagues remain dedicated to providing the critical monitoring, analysis and response that only regional networks can deliver.

During the SSA interview, an alarm sounded on Withers’ phone. Was that a new earthquake?

“Yes. A small one,” he said. “A 1.8 from Sweetwater, Tennessee.”