1 May 2024–When a magnitude 5+ earthquake occurs in the United States, the U.S. Geological Survey makes a variety of aftershock forecast communication products available to the public. But is there an ethical responsibility to make aftershock products more widely available to people affected by earthquakes in other countries?

In listening sessions held in 2022 and 2023 with seismologists and earthquake responders from around the world, USGS social scientist Sara McBride and her colleagues got a glimpse of the possible ethical and social tensions around publicly communicating the international aftershock forecasts that the USGS produces.

“By and large, most of the science organizations that we talked to agreed that for developing countries that might not have the scientific capability to do aftershock forecasting in their country, this would be beneficial because aftershock forecasts help people cope and support good decisions during the response to a damaging earthquake,” McBride said. “And if we could help people during a disaster, do we have an ethical responsibility to do so?”

“But alternatively, some people did not want the USGS to release aftershock forecasts in their country,” she added. “It was kind of, ‘it’s a good thing for others but we are not sure we want this for our country.’”

McBride spoke about the ethical challenges of communicating aftershock forecasts internationally at the Seismological Society of America (SSA)’s 2024 Annual Meeting.

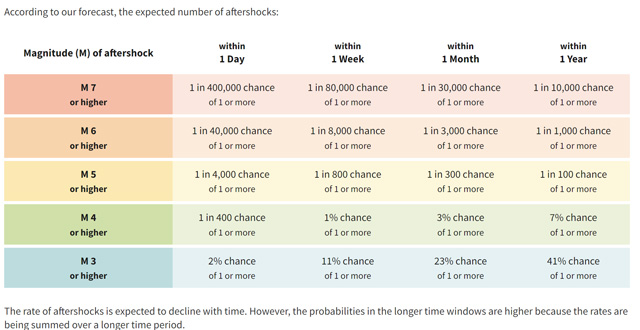

For larger U.S. earthquakes, the USGS produces a publicly available aftershock forecast on its products page for the earthquake in question. This probabilistic forecast, based on thousands of observed earthquake sequences and observations from the current one, presents data about where, when and how many aftershocks people can expect. And importantly, the product also offers information about what to do in case of aftershocks.

At the moment, the USGS can develop a forecast for an earthquake outside the United States to assist agencies during emergency response, on request.

The aftershock product was designed using social science research, McBride said. “We know that people who experience damaging earthquakes or significant shaking can experience a great deal of trauma, so we designed the aftershock forecast so that the first thing it says is, ‘be ready for more earthquakes. When people are in an unsettled state, simple messages are best.’”

“We also know from research that it is less effective to give people probabilities and bad news without giving them something comprehensive and useful to do about it,” she added.

The USGS aftershock product displays its information in a variety of tables, interactive visualizations and a news-like narrative, offering many ways for the public to interact with the information when they need it.

“Because if people can’t take onboard all the probabilities and the numbers and information, at least they know what to expect in the coming days, weeks, months and potentially years,” McBride said.

The 2018 magnitude 7.1 Anchorage, Alaska earthquake, McBride noted, was one of the first times she and the other developers of the USGS aftershock report could observe “how people were making meaning of the aftershock forecast.”

Research shows that people do find the information valuable, but there are challenges to expanding it for the public when it comes to international earthquakes.

For instance, “is it OK to forecast in other countries that we do not have scientific or social responsibility for? Would it be a kind of scientific colonialism?” McBride asked. During the listening sessions, she and her colleagues found “there was tension in our scientific community about whether we should do this or not,” especially regarding the scientific sovereignty of nations to produce their own forecasts.

McBride pointed out that in other sciences like meteorology, however, foreign nations do share models in other countries—such as the “European model” for hurricanes widely shared in the United States.

There is also the potential for miscommunication due to cultural and language barriers, she noted. “Communication is hugely cultural and language can be complicated when communicating about earthquakes,” McBride noted, especially when explaining the differences in terms like “forecast” versus “prediction.”

The USGS has no current plan to create and share a public aftershock forecast for international earthquakes, but the listening sessions will help guide the process if the forecasts are shared in the future, she said.